A Night In The Show next previous

A Night in the Show Clippings 3/54

Punch, London, September 1, 1915.

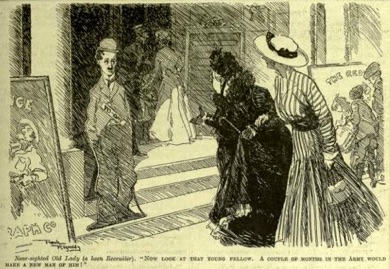

Near-sighted Old Lady (a keen Recruiter). „Now look

at that young fellow. A couple of months

in the army would make a new man of him!“

(...) Cartoon, Punch, London, July 28, 1915

„Charlie Chaplin is crossing the equator“

Editorial content. „Charlie.

For weeks there has been no escaping him. Nations might

be at each other‘s throats; Zeppelins might be dropping

bombs upon sleeping families; hopes and fears might make

hearts beat faster, while a sense of calamity filled the air;

yet all the time his claims as a gravity-remover in excelsis have

met one‘s eyes at every turn. Sometimes they were

fortified by effigies of himself, both life-size and gigantic,

a representation of one of which recently found its

way into a drawing in Mr. Punch‘s own pages. More than one

weekly paper has been printing his autobiography

serially.

The time clearly having come to investigate this

personality, I entered a cinema theatre which promised a play

with the famous man at his best. And than I entered

others, for Chaplinism had caught me.

Whether or not Charlie Chaplin is, as is claimed for

him by certain not disinterested people, the ,funniest

man on earth,‘ I leave to others to decide. Two persons rarely

agree on such nice points, and I retire at one from

arbitrament because I don‘t know all the others. But that

he is funny is beyond question. I will swear to that.

His humor is of such elemental variety that he would make

a Tierra del Fuegan or a Bushman of Central Australia

laugh not much less than our sophistical selves. One needs no

civilized culture to appreciate the fun of the harlequinade,

and to that has Charlie, with true instinct, returned. But it is the harlequinade accelerated, intensified, toned up for the

exacting taste of the great and growing ,picture‘ public. It is also

farce at its busiest, most furious. Charlie has brought

back that admirable form of humor which does not disdain the

co-operation of fisticuffs, and in which, by the way of

variety, one man is aimed at and another, too intrusive, is hit.

However long the world may last, it is safe to say that

the spectacle of one man receiving a blow meant for another

will ever be popular. Indeed the delivery of blows at all

will ever be popular. Thus – glory be! – are we built.

What strikes one quickly is the realization of how much

harder Charlie works than any other of the more illustrious filmers.

He is rarely out of the picture, and he gives full measure.

In the course of five minutes he receives and distributes a myriad

black eyes, a myriad falls. He kicks abundantly and is

abundantly kicked. He runs and is pursued. There is no physical indignity that he does not suffer – and inflict. Such

impartiality is rare in drama, where usually men are either

on top or underneath. In the ordinary way our pet

comedians must be on top – as, for example, Mr. George

Graves with his serenely conquering tongue. Even

the clown, though he receives punishment en route, eventually

triumphs. But Charlie Chaplin seldom wins. Circumstances

are too much for him, and he goes out in a very riot of grotesque

misfortune. With him, however, are always our sympathies.

These and a triffle of £500 a week (if the paragraphs tell the truth)

are his only reward; for of course he cannot hear. Yet

I suppose no one man has, in the same space of time, ever

made so many people laugh as he. Whether his fellow

cinema actors laugh I cannot say. But everyone else does.

It is a curious thought that Charlie does not hear it.

In the pictures Charlie has no immediate rival, although

on the actual variety stage I have seen several drolls

very much in his tradition, which is associated with the name

of Karno. One detects the Karno brand at once, but

in Charlie Chaplin, on the synthesizing film, it has an extra drop

of nervous fluid. He has none of the bland masterfulness

of the urbane and adventurous Max Linder; he has none of the

massive repose of the late John Bunny; he is without the

resource of the Italian Polidor. He remains a butt, or, at any

rate, a victim of circumstances whom nothing can

discourage or deter. His very essence is resiliency under

difficulties, an unabashed and undefeatable front.

By gestures rather than facial play does he gain his ends – gestures allied to acrobatic gifts of no mean order. He has

a host of comic steps, a thousand odd movements of his hands

and head, which when brought into play under domestic

or social conditions, are absurdly funny. With his hat, his stick

and his cigarette he has also a vast repertory of quaint

actions; and it was a wise instinct that caused him always to

appear in the same costume. But his especial fascination

is that life finds him always ready for it – not because he is armed

by sagacity, but because he is even better armed by folly.

He is first cousin to the village idiot, a natural child of nonsense,

and, like Antaeus, every time he rises from a knockdown

blow he is the stronger.

The promise of Chaplin is sacred; the promise of John

Bradbury is not more so. Seeing him, one is assured

that he is about to make hay of all the other dramatis personae.

One may sit back safely and prepare for fun. He joins

the film in his unobtrusive methodist way as quietly as a smut

settling on a nose, and behold he is the very spirit of

discord, the drollest of all the lords of misrule. Whereever he goes Charlie Chaplin is crossing the equator.“

Quoted in Evening Public Ledger, Philadelphia,

December 18, 1915.

Redaktioneller Inhalt

A Night In The Show next previous