The Bank Clippings 39/46

J. B. Hirsch, Motion Picture, New York, January 1916.

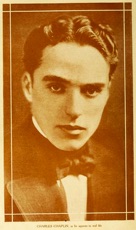

Charles Chaplin, as he appears in real life.

(...) Photo, Motion Picture, Jan. 1916

& The Bank Scene

& National, Local and State Censorship

(...) Cartoon, Motion Picture, April 1916

„This has the approval of the Board of Censors“

Editorial content. „The New Charlie Chaplin

By J. B. Hirsch

Here´s´a new Charlie Chaplin! The most universally known slapstick comedian of the film has burst the tawdry

chrysalis of that Charlie Chaplin of the English music-hall

manner and manners. The old Charlie Chaplin has

seen that the very methods by which his personality achieved

success now imperil his unprecedented reputation

by alienating a great part of the American public, to whom

the novelty of his fun-making appeals less as

familiarity with his farce bares offensive vulgarities. He has

realized the menace to his popularity, which has made

him not at all ,up-stage,‘ and pursues a new fame, to be built

on the basis of a more delicate art that will not

countenance the broad sallies his old technique demanded –

methods that his new metamorphosis eliminates

as not in keeping with the American conception of humor.

This is the impression of the National Board of Censorship,

gained by W. W. Barrett, of the executive staff of the

board, in an interview recently with Mr. Chaplin in the Essanay

studios in Los Angeles. Mr. Barrett, who returned

the early part of this week from a tour of the United States

made in the interests of the censorship board, had

much to tell about his experiences with many of the world‘s

greatest Motion Picture directors and actors. Charlie

Chaplin, the director, actor, writer and manager of his own

pictures, impressed Mr. Barrett more than did any

of the other screen personalities with whom he came

in contact.

Secretary Barrett explained that the National Board

of Censorship had taken an unusual interest in Chaplin‘s work,

and expressed his belief that there are great possibilities

in the comedian‘s future work, both as a helpful influence in a

community and as a factor in the artistic development

of the Motion Picture.

An intimate afternoon spent with Chaplin in and about

his studio served to convey to the censor impressions

of Charlie Chaplin, not as we see him – cutting up funny capers

and making faces – but ,close-up‘ impressions which

revealed Chaplin the artist and the business man. His critic

found him to be – unlike and contrary to his stage

appearance – a neatly and stylishly dressed young man;

as charming and affable a boy – for he appeared

to be but a youth – as anyone would wish to meet; a hard

worker, who writes, acts, produces and manages;

an unusually intelligent man, modest, not in the least

affected by his great popularity, and very keen,

businesslike and thrifty – not at all like the usual actor of the

,get-rich-quick‘ variety. Such is Charlie Chaplin as the

National Board of Censorship sees him.

A heart-to-heart talk between Mr. Barrett and Chaplin

revealed to the former the comedian‘s thoughts

and plans for the future. According to Mr. Barrett, Chaplin, who

is only twenty-five years old, is very ambitious. He has

shaped for himself the slogan, ,Art for art‘s sake,‘ and he has

dreams of unmeasured possibilities for the future of the

films – all from an artistic point of view. When he talks of the

change he intends to make in his style of farce,

it is in a very serious vein. He spoke thus to the censor man:

,It is because of my music-hall training and

experiences that I am by force of habit inclined to work into

my acting little threads of vulgarisms – not to hurt any

one, but, in my opinion, and from an artist‘s point of view, enough

to render the picture vociferous and inartistic. The

Elizabethan style of humor, this crude form of farce and

slapstick comedy that I employed in my work, was

due entirely to my early environment, and I am now trying

to steer clear from this sort of humor and adapt

myself to a more subtle and finer shade of acting.‘

Mr. Barrett explained that Chaplin‘s desire is to give the

American public the best that is in him. That there

is latent in Chaplin a great force of original and productive

material is the belief of the National Board of Censorship,

and the sooner the new style of farce – is adopted by him, the

sooner will there will be a realization of the better kind

of Motion Picture farce. Chaplin admitted that the evolution

of acquiring this newer and better style of acting is a

slow and laborious process, after so many years of music-hall

training; but that it eventually will be achieved by him

is his one consolation. One of his latest releases, The Bank,

already has given evidence of Chaplin‘s tendency

toward straight comedy. Chaplin, as an exponent of realism

and spontaneity without equal, the Board of Censorship

believes, is only on the crest of his popularity wave. But Chaplin

is very candid and reticent about his own work, and

would not agree with Mr. Barrett that there was no Chaplin

equal. He feels that his Brother Sydney is just

as clever.

,Charlie Chaplin attributes his success,‘ said Mr. Barrett,

,to the novel character of his mannerisms, adapted

from his pantomime experience. He bases his actions on little

traits of human interest and eccentricities. He believes

that the prolonged portrayal of the inebriate on the screen, and

some of his actions when in a drunken stupor, are not

really funny; they are extremely sad, to use his own words. But

what Chaplin does believe in, and what went a great

deal toward making his success, is the portrayal of a drunkard

by human-interest touches, funny little capers that

any well-meaning man in an intoxicated condition is likely

to penetrate. This has the approval of the Board

of Censors.‘

Mr. Barrett, as it was stated in the beginning, made

a tour of the country, and particularly of the West,

in the interests of the National Board of Censorship, to effect

a correlation between the board and the country‘s

film producers on the basis of cooperation. Some sort of spirit

of co-operation had existed heretofore, but it lacked

so much in mutual interest and genuine co-operation that

a better and firmer system of reciprocal and effective

censorship had to be established. Hence Mr. Barrett‘s tour

of the country.

Directors such as Griffith, Ince, Sennet(t) and Reicher

were interviewed and acquainted with the board‘s

delimitation of the scope of the censor‘s work, and such

general information that would result in nothing but harmonious

co-operation between the manufacturer of films and

the censors. The Board of Censorship feels that directors

four thousand miles away often get out of touch with

the work of the board, and when a producer loses sight of the

censorship in the making of a film he is sometimes

hastening the destruction of his own production and throwing

away his firm‘s money.

Charlie Chaplin, as a producer, agreed with the National

Board of Censorship‘s representative that, if there must

be a board of censors, the present National Board was the one,

not any other. He expressed his belief that there should

prevail the existing system of constructive cooperation between

film-makers and the people, thru criticism of films

by a board of volunteers that reflects current morality in its

decisions as ably as that difficult thing ever has been

done. Mr. Chaplin prefers that kind of censoring to the one

that is nothing but a system of legal censorship by

small local boards of untrained individuals appointed for

limited terms and possessing limited ability, but

unlimited destructive power.“

Redaktioneller Inhalt