Charlie Chaplin´s Burlesque on Carmen next previous

Burlesque on Carmen Clippings 30/101

San Francisco Examiner, San Francisco, California, March 19, 1916.

Geraldine Farrar as The Cigarette Girl in „Carmen.“

(...) Photo by Aime Dupont,

San Francisco Examiner, March 19, 1916

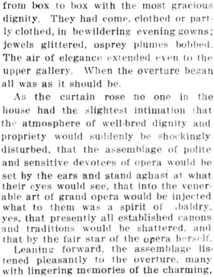

& Scene from Carmen on the

Metropolitan Opera House Stage – Caruso Standing Over

the Prostrate Form of Carmen (Miss Farrar)

(...) San Francisco Examiner, March 19, 1916

„She had Charley-Chaplinized the most sacred of the arts“

Editorial content. „Charlie Chaplin‘s Influence

on the Grand Opera

How Geraldine Farrar, Impressed by the Instructions

of Her Motion Picture Director, Introduced

,Rough-House‘ Methods Into Her New Interpretation

of ,Carmen‘ to the Dismay of Caruso, Who

Pushed Her Off Her Feet – and Got His Face Slapped!

Charlie Chaplin Who Was Pointed Out

to Geraldine Farrar as an Excellent Model for Live-Wire

Actions When the Motion Picture Stage Director

Complained That Her Old-Fashioned, Conventional Grand-Opera Acting Would Never Do In Moving Pictures.

WHEN Geraldine signed her contract to do a photo-play

of Carmen, her most famous grand-opera success,

the managers of the motion picture company had misgivings.

Could an opera, which depends upon the voices

of the singers and a magnificent orchestra, be a success

in motion pictures? „Leave that to me,“ said the

stage director.“

Lasky‘s Carmen starring Geraldine Farrar was

directed by Cecil B. DeMille.

„When Geraldine Farrar some months ago made her

appearance at the motion picture studio dressed

for the part of Carmen she began to go through the part

exactly as she has always done on the Metropolitan

Opera stage in New York.

,We‘ll stop right here,‘ said the stage director. ,I‘m afraid

that won‘t do.‘

,No?‘ Miss Farrar queried.

,On the opera stage you are the greatest ever,‘ said the

stage manager, ,but in motion pictures we‘ve got

to do some real acting.‘

,Yes? But this is the way I have always done Carmen.‘

Mme. Farrar returned, with perfect good nature.

,Nobody does any real acting in an opera. When you sing

Carmen people go to hear the music. In the movies

people want to see some acting. Did you ever see Charlie

Chaplin?‘

,Why, certainly – he is superb.‘

,Something Doing All the Time.‘

,Well, just forget Caruso and his big voice and imagine

Charlie Chaplin playing opposite you in Carmen.‘ You

know what he would be doing all the time, and you can figure out

what you would have to be doing to keep your end up.‘

,Oh, I see what you mean.‘

,Kicking, punching, biting, scratching – something doing

all the time. Of course I don‘t mean to say that every

reel has got to be a rough-house. But you can‘t sing a part

in motion pictures, and those foolish grand opera

motions are not acting.‘

,That is very interesting,‘ Mme. Farrar smiled.

,Who was Carmen? She was a girl who

worked in a cigarette factory. When factory girls have a row

it is no Fifth avenue drawing room afternoon tea.

When factory girls fight they put up a real fight – pull hair, use

their fists, tear their clothes, roll over on the ground,

bite and kick – you are playing the part of a cigarette girl

in this piece.‘

,I see,‘ said Mme. Farrar thoughtfully. ,No doubt your

interpretation is right. Let us start all over again.‘

–

The largest audience of the season filled the Metropolitan

Opera House, New York, the other night – that august

temple of grand opera – to hear Mme. Geraldine Farrar and

Signor Enrico Caruso at the first performance given

this season of Bizet‘s Carmen. An air of well-bred expectancy

prevailed throughout the house. In the horseshoe

of boxes refined and lovely ladies, leaders of New York‘s

ultra fashionable set, chatted softly and amiably and

bowed to one another from box to box with the most gracious

dignity. They had come, clothed or partly clothed,

in bewildering evening gowns; jewels glittered, osprey plumes

bobbed. The air of elegance extended even to the

upper gallery. When the overture began all was as it should be.

As the curtain rose no one in the house had the

slightest intimation that the atmosphere of well-bred dignity

and propriety would suddenly be shockingly disturbed,

that the assemblage of polite and sensitive devotees of opera

would be set by the ears and stand aghast at what

their eyes would see, that into the venerable art of grand opera

would be injected what to them was a spirit of ribaldry,

yes, that presently all established canons and traditions would be shattered, and that by the fair star of the opera herself.

Leaning forward, the assemblage listened pleasantly to the

overture, many with lingering memories of the charming

quiet Carmen which Mme. Farrar had presented a year before,

some of the older supporters of grand opera with

memories of the classic Carmen of Mme. Calve. Ah, that

Carmen of Mme. Calve! Vivacious – but not too

vivacious!

The beautiful music of Bizet sparkled and entranced.

Then, abruptly, as occurs in the opera, the door

of the cigarette factory opened and Carmen, disheveled,

fighting with the other cigarette girls was precipitated

on the stage. But the Carmen that appeared was not the Carmen

the polite Metropolitan audience was accustomed to.

The Carmen to whom they were accustomed came out of the

factory disheveled, her clothes torn – but not too much

torn. The Carmen that appeared was in an underwaist and skirt,

the skirt ripped and frayed, bearing all marks of a vicious

row, and, moreover, there was a smear of blood on her left sleeve.

A smear of blood! The elegant audience gasped.

More, the moment Mme. Farrar appeared Carmen had

changed. Her eyes blazed, her face contorted, every

muscle of her was alive. Before you could say ,Jack Robinson,‘

she had floored one of the cigarette girls, and then,

before their eyes, that assemblage of 3,000 saw America‘s

fairest prima donna, one of the stars of the venerable

Metropolitan, roll over her fallen antagonist, grapple with her,

pummel her with her fists, pound her and actually bite

her. But what was their amazement when, rising, she gave the

girl a vicious kick. Then, like an inebriate woman

of the gutter, who challenges all of her neighbors to leave

their washing and engage if they will with her fistically.

Mme. Farrar staggered about the stage – that stage hallowed

to Parsifal and Tristan – shaking her fists, clenching

and unclenching her fingers, and defying any other girl to come

along if he shared.

The assemblage glared agape. To some, Mme. Farrar

was giving new life to opera. She was putting a punch

into Carmen literally and effectively. She sang irreproachably,

and in addition she acted – but to many shockingly.

Along the glittering horseshoe fair ladies, their heads bobbing

with osprey plumes, gazed at one another with well-bred

but restrained amazement; indeed, some whispered their surprise

and dismay at such behavior on the part of the lovely star.

And while they stared stonily, disapprovingly, Mme. Farrar lurched

and reeled about the stage.

She was never at rest. She moved constantly. Her eyes

roved about. The muscles of her face twisted with

a changing constant play of expression. At first the audience

did not quite realize what was happening; they did not

quite know how to take Mme. Farrar‘s performance. They listened

and waited. And then the most amazing, most audacious

thing occurred.

The poor girl of the unnamed chorus had limped away with

her bites and bruises. Don Jose (Caruso) appeared,

and Carmen, as the action proceeded, began to coquette.

But this time she coquetted as no Carmen of the

opera had ever coquetted. Indeed, to many of the elegant ladies

in the boxes there was something unseemly in her

abandonment. They were not, it is true, quite pleased.

Presently the time came for Carmen to fling

her rose into the face of Don Jose. The audience expected

to see Mme. Farrar fling the rose as Calve had done

it, as she had done it a year before. Caruso expected to have that

rose flung in his face – but lightly, gently, conventionally.

What a surprise of that audience, what was the aghast horror

and indignation of the great golden-throated one

himself, the incomparable Caruso, when, instead of lightly tossing

the rose, the fair Farrar‘s hand smote his face

a resounding whack!

,Oh!‘ An audible gasp arose from the house. The great

golden-throated one, the incomparable Caruso,

his eyes blazing their rage, staggered away, ruefully rubbing

his cheek. His face was red from the fair prima

donna‘s terrific right-hander. he was so started, so dum-founded,

so indignant that he could hardly sing.

Every one in the house had seen it. All society – including

the Goelets, Harrimans, Ogden Millses, Havemeyers,

Iselins, Gallatins, etc. – were surprised and shocked. Such

realism had never before been seen on the grad

opera stage.

For a violation of the traditions of grand opera, to the patrons

and supporters of grand opera, is like the violation

of a commandment. The tradition goes that opera must be sung

– not acted, and that it must be performed with dignity.

From prima donna to chorus singer and ballet performer it must

be done along certain lines, in such a particular way,

without a departure into new business. ,Tra-la-la,‘ sings the

prima donna, lifting her right arm, woodenly and

putting one foot forward stodgily. ,Tra-la-la,‘ sings the chorus

lady, lifting the left arm, and extending the right foot.

,Lalala! Lalala!‘ sing the chorus, moving forward and backward

with measured step.

Actually Slapped Caruso‘s Face.

Only as Mme. Farrar‘s performance progressed did the import

of what they beheld dawn upon the assemblage. For

what had first shocked them was only the beginning of surprises.

When she laughed, Mme Farrar laughed as Carmen

had never laughed. It was the vulgar laughter of a factory girl.

She made Carmen realistic.

Caruso sang, and while he sang Mme. Farrar moved about.

If she was not walking, her eyes were moving, or her arms

were in action. She swayed her hips, smiled, scowled, tossed

her head. There came the scene in Lillas Pastia‘s inn.

What was the astonishment of the audience when Mme. Farrar

threw herself full length upon a table. What was their

further amazement when, again, she sat cross-legged – like

any common girl of a city‘s slums. Meanwhile, it was

visible to all that the great Caruso was becoming more and more

irritated, more and more angry.

While he was singing a beautiful and difficult aria – when,

of course, according to all traditions, every eye should

be fastened upon him, every ear listening – Mme. Farrar attracted

attention to herself by moving about. She took the spotlight

from the tenor. As Caruso sang his eyes sometimes fell on the

fair agile Carmen, but with a glare not in keeping with

even a stage lover. Now and then, it is said, his golden voice

trembled. Mme. Farrar was never in repose. Those

who sympathized with Caruso, smarting under the blow, admired

the great one‘s restraint.

After the first act it could be observed that part of the

audience clapped and cheered, while others were

ominously silent. Mme. Farrar had committed the unutterable

thing – she had acted in grand opera! Worse, she

had Charley-Chaplinized the most sacred of the arts. She had

shattered the inviolable traditions of dignity with

the common business of the movies! She had engaged

in a dust-biting Charley Chaplin fracas. She had

brought back with her from her career as a movie actress

that business of constant movement necessary

for the reel. She had slapped Caruso‘s face, just as Charley

Chaplin engages in face-slapping stunts. She had

realized by acting a living Carmen! Instead of the set movements

and elegant repose necessary even in such a part,

she was eternally in action. She moved about even during

a prayer.

The climax, however, was reached only in the third act,

when, while Don Jose sings impassioned emotional

music, Carmen is supposed to cling to him. But Mme. Farrar

did more than cling. She acted fervidly, madly,

passionately. She clutched the great one of the golden voice

and pressed herself to him painfully. She gripped

him so frantically he lost his breath. He could hardly sing.

His face reddened. he glared at Mme. Farrar in rage.

Still he sang, though with difficulty. Mme. Farrar‘s embraces

tightened and tightened. Unable to roll out the golden

notes, the incensed Caruso suddenly forcibly seized Mme. Farrar‘s

both arms and held her from him in a vise-like grip.

She struggled, but he was the stronger.

They tussled, while the audience gazed in bewildered

incredulity, and finally, with a free swell of liquid notes,

the song ended. Then – quite commonly, quite vulgarly – the

great Caruso carried beyond himself by the indignity

of the blow, the distraction of the star‘s movements and her

interference with the golden flow of song, suddenly

released his grip and pushed Mme. Farrar forcibly, vigorously and

rudely from him. Thump! And down to the floor, with

a resounding bump, fell the vigorous Carmen of the movies.

They Glared at Each Other.

But back of the stage things were no less exciting.

The curtain fell. While the audience, expressing

their well-bred surprise, were rising to depart, Caruso and Mme.

Farrar met in the wings as they were going

to their dressing rooms. Caruso, remembering the vigorous

right-hander, glared. Mme. Farrar, smarting from

her bump, glared.

,If you do not like the way I play the part,

Mr. Gatti can get another Carmen,‘ the

fair prima donna is reported to have retorted.

The great tenor bowed mockingly,

and replied with biting politeness:

,No, my dear Mrs. Tellegen, on the contrary,

he can look for another Don Jose.‘

The sentiments of the conventional and proper

supporters of grand opera were unanimously

expressed by the musical critics the day following Miss Farrar‘s Charley-Chaplinized performance of Carmen.

The ,movie-Carmen‘ of Mme Farrar, according to these,

had become ,a common drab, a plebeian Messalina.‘

The punch and ginger Mme. Farrar had put into this conventional

role to adherents of tradition was ,common, low and

vulgar.‘ The part ,was cheapened and vulgarized.‘ Mme Farrar‘s

performance was ,rough and tough.‘ ;She had gone

beyond all bounds.‘

Has Geraldine Farrar introduced the little leaven which

will leaven the whole loaf of grand opera? What

is Art? Nobody agrees on the answer. Why should the

conventional rules of acting of the grand opera

persist? If cigarette girls scratch and kick and bite, why shouldn‘t

the opera personification of Carmen scratch and kick

and bite? Has the influence of Charlie Chaplin working through

Mme. Farrar come to lift the grand opera out of its

conventional monotony?

Copyright, 1916, by the Star Company.

Great Britain Rights Reserved.“

Redaktioneller Inhalt

Charlie Chaplin´s Burlesque on Carmen next previous