The Cure Clippings 2/70

Mabel Condon, Picture-Play, New York, December 1916.

Mabel Condon, Manager

(...) Motion Picture News, July 22, 1916

& The Mabel Condon Exchange

(...) Motion Picture Studio Directory and Trade Annual, April 12, 1917

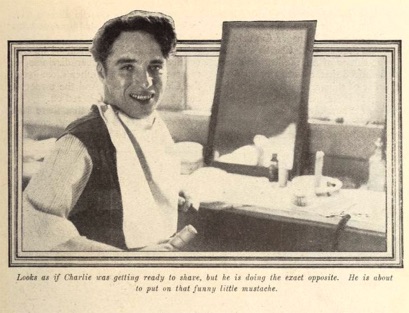

& Looks as if Charlie was getting ready to shave,

but he is doing the exact opposite. He is about to put on that

funny little mustache.

(...) Photo, Picture-Play, Dec. 1916.

„Comedy is such depressing work“

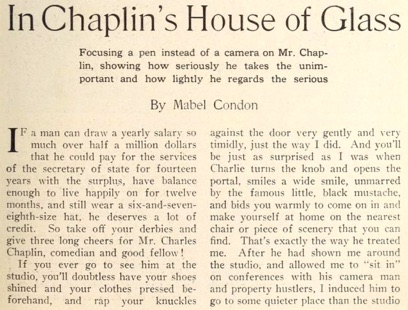

Editorial content. „In Chaplin‘s House of Glass

Focusing a pen instead of a camera on Mr. Chaplin,

showing how seriously he takes the unimportant

and how lightly he regards the serious

By Mabel Condon

IF a man can draw a yearly salary so much over half

a million dollars that he could pay for the services

of the secretary of state for fourteen years with the surplus,

have balance enough to live happily on for twelve

months, and still wear a six-and-seven-eighth-size hat. So take

off your derbies and give three long cheers

for Mr. Charles Chaplin, comedian and good fellow!

If you ever go to see him at the studio,

you‘ll doubtless have your shoes shined and your clothes

pressed beforehand, and rap your knuckles

against the door very gently and very timidly, just the way I did.

And you‘ll be just as surprised as I when Charlie turns

the knob and opens the portal, smiles a wide smile, unmarred

by the famous little, black mustache, and bids you

warmly to come on in and make yourself at home on the

nearest chair or piece of scenery that you can find.

That‘s exactly the way he treated me. After he had shown

me around the studios, and allowed me to ,sit in‘

on conferences with his camera man and property hustlers,

I induced him to go to some quieter place than the

studio stage and tell me something about himself. The q. p.

was the big, comfortable office of Manager Caulfield,

of the Lone Star studio. Charlie slid into the far corner of a

large leather divan, and I noticed that, contrary

to the natural order of things, he was the one that was

nervous, instead of me.

,I – I get horribly embarrassed,‘ confessed Charlie,

turning his six-and-seven-eighth panama round

and round and adjusting the black ribbon band thereon that

needed no adjusting. ,I – I‘m very ordinary. So ordinary

that there isn‘t a thing for me to talk about concerning myself.

If you want a story about my success, all all that, you

don‘t want an interview with me – you should be introduced

to my flexible bamboo cane and my little mustache.

They are in their dressing room now, resting, and I‘m perfectly

sure that they wouldn‘t mind having you consult them.‘

I laughed, but Charlie didn‘t. He looked as though he half

meant what he had said.

The panama hat seemed, of its own volition, and from

sheer dizziness, to reverse and spin the other direction

in the Chaplin hands. And the owner of both hat and hands

faltered on.

,I – I‘m so ordinary that there isn‘t a thing for me to talk

about, concerning myself. I suffer whenever I meet

a reporter, or interviewer. if they only weren‘t going to write

what I said – or if they only wrote what I said! I don‘t

know just which is the worse. I always feel as though I should

have some wonderful things to say –and I never have.‘

The Chaplin hat, now traveling between the Chaplin fingers

at the rat of at least thirty miles an hour threatened

to fly from its fingered moorings and depart one might never

know where – or maybe into the corral, immediately

without the window, and where the Chaplin pet goat was

holding solitary but bleating watch. By way of

safeguarding the hat, and also to bring peace to the heart

and manner of Mr. Chaplin, I volunteered:

,Interviews are so obsolete, don‘t you think?‘

He thought.

,And questions? I never ask questions.‘

A great peace settled itself over all

things, and the Chaplin voice, though resigned, had no

intimation of interview resignation about it.

,Comedy is such depressing work,‘ was what he was

saying. ,You‘ll always find a gloomier atmosphere

about a comedy studio than elsewhere.‘

He sighed.

,When I feel that I can do just what I want to do, I‘m

going to do drama.‘

,But –‘

,Yes – but I‘ll try it, anyhow. Even if i don‘t please

anybody but myself in trying it, I at least will be getting a change

of work.‘

,But to be able to make people laugh –‘

,That‘s just it,‘ eagerly took up Charlie, ,but does one

continue to make people laugh? That‘s always the

comedian‘s nightmare – that the time will come when they

won‘t laugh.‘

,Oh, they laugh!‘ I assured him, feeling of some assistance

in being able to truthfully say so.

,I hope so,‘ Charlie said, referring to the laughs and

people. ,I work hard to make them laugh – and I get

more temperamental every day. I wish‘ and he emphasized

the wish with a frown at the goat and a lemonless

lemon tree that reigned supreme outside the window – ,I wish

they wouldn‘t let me get temperamental. I don‘t want

to get temperamental,‘ he objected. ,But it‘s just because

people try to save me from so many things that

might be annoying. it makes me so self-conscious, being taken

care of that way.‘

,No, I‘ll never get used to temperament – or may pay check.‘

I suggested that the latter must be something of a

weekly shock, and the recipient of the shock agreed that it was.

,My ambition, when I started picture work, was

to make enough money, some time, so that I might retire with

the knowledge that I had enough to insure me a

twenty-five dollar-a-week income for the rest of my life. I was

sure, then, that I would be satisfied and happy with

that. My first contract, with the Keystone Company, was for

one hundred and seventy-five dollars per week.

I showed it to everybody I knew, and inwardly quaked with

the fear that I would never be able to fool them

into paying me that much for more than a few weeks. When

I had been there three months, I had some confidence

in myself, and knew enough to refuse an additional couple

hundred, knowing I could get more. I did. And

now that I‘ve got it, I don‘t know what to do with it.‘

A this sad statement, the sun, deciding

to sink behind the Hollywood foothills, threw a shaft of

brightness across one Chaplin food extended

in its grey-topped black shoe, and appearing radically

unChaplinesque in its neat smallness. Charlie

seemed to reflect upon this, and then proceeded.

,I don‘t spend much oft it,‘ referring to the

ten thousand a week plus a bonus. ,What might I buy?‘

he asked, as though hoping some one would

tell him. ,One thing that I have bought is service – valets

and things. I do love service,‘ he explained,

adding: ,There are so many things I have to do myself

that when I can buy anything to be done for me

I‘m glad to do it.‘

,Things haven‘t come easily to me all my life,‘ he offered,

reflectively dancing the foot in the sun motes. ,Things

were always rather hard. I was one of the unfortunate kind

who works hard for little money. I was known as

a good actor, but I never got any salary for it. I became

so that I didn‘t expect any – so when it did come,

it was quite extraordinary.‘

,The whole thing, though – playing, directing, and

thinking up something funny where funny things

never were – is a tremendous responsibility. I get depressed

thinking of it. You see, it‘s like this I should hate to think

that my pictures weren‘t making money for the firm releasing

them. My pride wouldn‘t stand that. So I try to think

up new laughs for new pictures all the time, and go at making

them as though I knew when I started just what I was

going to do in them.‘

,Suppose, though, you were going to take a long vacation

– then what?‘ And the fun man, who would give a great

deal to be entertained by some one as he himself entertains

millions, replied:

,Russia. The thought of it fascinates me.‘

,But how about an English castle – and a title, maybe?‘

And Charlie laughed a laugh of startlingly white

teeth and a forgetfulness of the problem of what to do with

his money, as he answered:

,Wouldn‘t my derby hat, loose trousers, big shoes, and

thin stick placed crosswise, make a wonderful coat

of arms on the carriage of ,Sir Charles Chaplin?‘ I‘d have

to buy in all the Charlie Chaplin prints – especially

the Tillie‘s Punctured Romance one, where all I did was kick

Marie Dressler. All though the making of the six

reels I was exhorted to ,Kick Marie Dressler.‘ And I did.‘

A plaintive bleat came through the window.

,My goat – he‘s hungry,‘ interpreted Charlie, and we walked

forth to greet the goat. It raced at us, a series of

brown-and-white leaps until brought to a sudden and violent

halt by the limitation of its rope.

,He‘s hungry,‘ repeated Charlie, patting the animal

affectionately as it stood on its hind legs and

imprinted clay hoof marks on the matty dark-blue shoulders

of the Chaplin well-fitting suit.

From a stout man, in a red sweater and the wings

of a set, came the remark:

,Hungry? I‘ve fed him bushels of everything all day!‘

,So‘ve i,‘ came another voice, as another

besweatered individual hove into sight, armed with a hammer

and nails.

,Oh, Charlie!‘ sang out Mr. Caulfield, in a pleased-with-himself

voice. ,I just gave your goat a bag of cakes!‘ And there

was the slam of the Caulfield managerial desk as it was shut

for the night.

,But somehow,‘ reflected Charlie, as though puzzling

over a wonderful mystery, ,he‘s always hungry.‘

He left the animal, and walked into the studio.

A kitchen set supplied with much prop food, a hallway

set equipped with wide and suspicious-looking

balustrades, a saloon set, bearing the unconvincing

name ,The Bulldog Rest,‘ were visible, and

Mr. Chaplin, waving a nonchalant hand toward all, said:

,My sets for tomorrow. The story? Sh-h-h!

I don‘t know yet. I only started making the picture yesterday.‘

And that statement told exactly how Chaplin

works. Everything that goes into his comedies is done

on the spur of the moment. He made sure that

all was in readiness for the following morning, and then led

the way out again. I suggested that a few ,at-home‘

photographs would make fireside reading for the waiting world.

,My only home life is here in the studio.‘ He pointed

up at the paned roof. ,I‘m one of those chaps who live in glass

houses.‘“

Redaktioneller Inhalt