A Woman Clippings 37/72

Harry C. Carr, Photoplay, New York, August 1915.

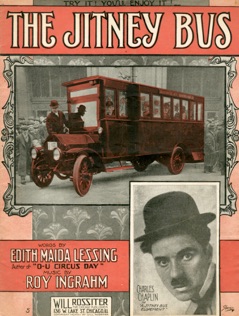

The Jitney Bus

Words by Edith Maida Lessing, Music by Roy Ingram

Chicago, 1915, Margaret Herrick Library,

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Part 1

„By making the most of the little subtle effects“

Editorial content. „Charlie Chaplin´s Story

His Stage Career and Movie Beginning

By Harry C. Carr

Drawings by E. W. Gale

The first part of the story of Charlie Chaplin – in the July

issue – was a record of his early career as narrated

to Mr. Carr by Mr. Chaplin. Part III – In the September

Issue, will describe his experiences at the Keystone

studios, where he became famous.

Part II

After he became old enough to be a ,regular actor,‘

Charlie Chaplin didn‘t find the going very easy.

The irony of his fate was that, after all his training

by his mother for the career of a legitimate actor,

the only direction in which he really scored was in rather

rough comedy. His success, however, was in the

quaint touch that he brought to what had formerly been

pointless horse play.

Chaplin tells his friends that he knocked around from

pillar to post on the stage in England – sometimes

in one job, sometimes in another. He says that he was glad

to eke out a bare living. Most of the time he was working

in burlesque and pantomime. He ascribes his success in the

pictures to the early training that he got under the great

English pantomimists.

About 1910, Fred Karno put on a variety act called

A Night in a London Music Hall. It concerned the adventures

of a very badly spiflicated young swell in a box at a music

hall with the boxes at one side of the stage. The tipsy young

swell sat in one of these boxes. He tried to ,queen‘

all the beautiful ladies on the music hall vaudeville bill. Several

times he climbed over the edge of the box onto the

miniature stage. Most of the time, he was either falling into

or out of the box. The swell had to do about a million

comic ,falls‘ during the progress of the sketch, it was very funny

and ended in a riot of boisterous mirth.

In England, the part of the tipsy young person was

taken by Billy Reeves, a well known comedian who is now with

the Universal Film Co. The sketch made such a hit

that Karno finally decided to send it over to the United States.

Reeves proved to be a riot here and Karno organized

and sent over a No. 2 company to tour the Western States.

Charlie Chaplin was employed to head the No. 2

company. His salary was $50 a week.

Chaplin often tells his friends of his adventures when

he first arrived in the United States. It is enough

to say when he first looked upon us as a nation, he decided

that he would not do. He didn‘t think anything of us

that we would enjoy remembering.

Chaplin says that shortly after arriving in New York, he went

to a show in a vaudeville theatre. It happened that some

vaudeville actor was giving an imitation of an English Swell –

or at least what he thought was an English swell...

a regular Bah Jove one... one of these remarkable creations,

the like of which really never lived on earth. Chaplin,

who is a very serious person, was deeply offended. To say

he was peeved at this reflection upon his countrymen

is putting it mildly. As the sketch went on, Charlie got so indignant

he couldn‘t stand it any longer. He rose in his seat and

started a public protest. He never got any further than ,Oh I say,

there,‘ when some of his loving friends grabbed him

and removed him from the place before the janitor got a chance

to cave in his now celebrated countenance.

Charlie likes America now. He confesses that he finally

returned to England at the head of his No. 2 Night in a

Music Hall company and found that he had outgrown England.

He cheerfully admits that England couldn‘t see him at

all. The English are peculiar as theatre audiences. They cling

to the old favorites and resent new comers taking their

places. So Charlie, after vainly tumbling around on the stages

of his native land, exclaimed to his companions,

,For God‘s sake let‘s get back to the United States where

they know about us.‘

Chaplin‘s western tour was a huge success. He played

the Sullivan and Considine Circuit on the Pacific Coast.

To tell the truth he was simply a riot. In Los Angeles especially,

he made an immense hit. The word flew around the

,wise alleys‘ to ,go over to the Empress and see that drunk,

He‘ll kill you sure.‘ Chaplin made a special hit with

other theatre people. His rough comedy had in it a touch

of real thought and superiority and earnestness

that was recognized as something different. Every drunken

fall showed the planning of a fine brain.

Owing to the manner in which the word was passed

around among Theatre people, Chaplin was well

known to actors and to moving picture people around the studios

of Los Angeles for sometime before he went into the

business.

The year after he played his Night in a London Music

Hall, he came back to the Western States in another

sketch called The Wow Wows. In this he again took the part

of a swell drunk. In fact all Chaplin‘s early successes

were drunken ,dress suit comedies.‘

The Wow Wows was only fairly well received

and the following years he came out again in the London

Music Hall.

By this time, his sketch had become one of the most

famous in ten-twent-thirt vaudeville. During this third

year some one of the Baumann and Kessel people who own

the New York Motion company conceived the idea

of getting Chaplin to come into moving pictures. Mack Sennett,

who heads the Keystone Comedy Company was

consulted and approved of the idea. He was delegated

to sign up Chaplin.

Chaplin was then getting $75. Sennett called on him

at the Empress Theatre and offered him a prodigal

raise; he offered Chaplin a year‘s contract at $175 a week.

Chaplin was nearly scared to death.

A Los Angeles friend tells about it: ,One night Charlie

stopped me on the street and told me about the

offer. He was excited and didn‘t know what to do. He said

he was afraid to try as he didn‘t think he would make

good. The money, though, was a terrible temptation. He filled

and backed for a while, but finally decided to sign.

He was largely influenced to do this by the contract. I remember

that he kept saying, ,Well, you know they can‘t fire me

for a year anyhow. No matter what a flivver I make of it, they

will have to pay me my salary for a year anyhow.‘

Charlie played out his vaudeville engagement and went

out to the Keystone. He felt about as sure

of himself as a man going up in a flying machine.

To make this story right, our young hero should have

gone out to the Keystone and scored a triumph; but,

alas, the facts are agin him. His first days at the Keystone were

anything but happy ones. They didn‘t understand him

and he didn‘t understand them. Chaplin had been carefully

trained along the lines of English pantomime. He

found the silent drama a la American to be utterly different

in every particular. They didn‘t get effects the same

way. American comedy was, in those days, a whirlwind

of action without any particular technique. Charlie

was more shocked than he had been at the vaudeville actor

who mocked his countryman.

From all accounts he and the lovely Mabel Normand,

now the best of friends and the warmest admirers of

one another, got along about as well as a dog and cat with

one soup bone to arbitrate. He told Mabel what he

thought of her methods and Mabel told him a lot of things.

In those days Charlie used to come wandering

back of the scenes at the theatres as lonesome as a lost soul.

He was ready to chuck the whole business.

,They won‘t let me do what I want; they won‘t let me work

in the way I am used to,‘ he complained. His first

pictures for the Keystone were not much of a success. In one

of them he appeared in the part of a woman. Chaplin

was mis-fit in the organization. The directors couldn‘t understand

his particular style of comedy and things were going very

badly. Chaplin‘s did not fit into the Keystone comedies. A play

has to be especially built up to Chaplin‘s style.

Chaplin was a very likable chap, however, and was very

popular with the other actors. He was modest to a fault;

they liked him because he didn‘t try to hog either the film or

the scene. Also in a shy way, he taught them a lot.

In those early days, the art of the comic fall was not

well understood. The Keystone policemen were half

the time in the hospital. Actors suffered more casualties than

the German army. Chaplin had had a thorough training

in ,falls‘ from the trained English pantomimists. He knew exactly

how to do it. He very generously passed on this

knowledge to the sore and suffering Keystone police force.

The hospitals were the poorer thereby.

Also, the Keystone people began to see there was

something in Chaplin‘s methods worth studying.

Chaplin, on the other hand, began to adopt the American

film methods.

He never made a real success however, until Mack

Sennett let him direct his own comedies. Sennett is a very keen

judge of character and he saw that if anything was

to be had out of Chaplin, it must be had in Chaplin‘s own way.

He reconstructed the organization to enable Chaplin

to direct his own comedies.

Sennetts‘s decision brought into being the quaint

character with the little stubby moustache, the big

shoes and the cane that is known wherever motion pictures

are known.

Chaplin‘s first picture with the Keystone company

was a little comedy sketch called A Film Johnny. It was taken

at the first cycle car races given in southern California.

Chaplin had the part of a picture fan who was always wandering

out in front of the cameras that were trained on the

race. His part was merely intended to ,carry‘ the motion

pictures of a race.

A good many of Chaplin‘s earliest pictures with the

Keystone were of this character; he was used to put in incidental

business in big news events. In one news picture

taken at San Pedro Harbor, for instance, he was assigned

the part of a rough-neck woman who was very severe

with her husband.

The first picture that he directed himself was called

Caught in the Rain.

As a director, Chaplin introduced a new note into

moving picture. Theretoforemost of the comedy effects had

been riotous boisterousness. Chaplin, like many

foreign pantomimists got his effects in a more subtle way and

with less action. Also he worked alone to a greater

extent than any other picture comedian.

By making the most of the little subtle effects, Chaplin

enlarged the field of all motion picture comedies.

It goes without saying that the simpler effects a man needs

for his fun-making the more effects he has to draw

on. One of the very funniest situations, for instance, in any

of the Chaplin comedies was in His Trysting Place

where Chaplin used the whiskers of a guest in a cafe for

a napkin.“

One photo. One drawing. One comic strip.

The film with Chaplin wandering out in front of the cameras

is Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal., not A Film Johnnie,

and Kid Auto Races at Venice, Cal. is not Chaplin‘s first film

at Keystone. It was not „in those days“ that he was

working at Keystone, it was last year.

Harry C. Carr, Charlie Chaplin´s Story,

Photoplay, July 1915

Photoplay, August 1915

Photoplay, September 1915

Photoplay, October 1915

Redaktioneller Inhalt