A Woman Clippings 8/72

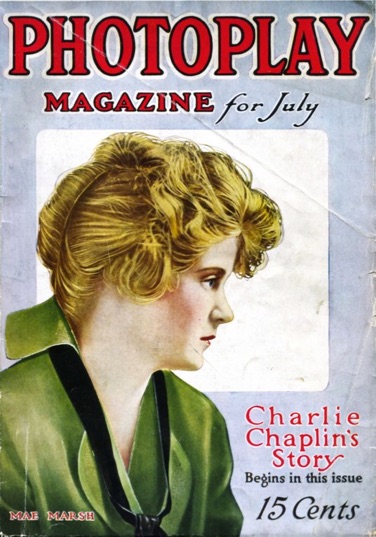

Harry C. Carr, Photoplay Cover (Mae Marsh), New York, July 1915.

MOVING PICTURES (...)

CABANNE THEATER (...) Monday, Chas. Chaplin,

in „A Woman.“

NEW FAVORITE (...) Friday and Saturday, Charlie Chaplin

in „Women,“ newest Essanay release; two parts.

PLAZA THEATER (...) Monday, Chas. Chaplin in his latest

comedy, „A Woman.“

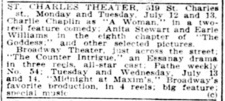

St. CHARLES THEATER (...) Monday and Tuesday, July 12 and 13, Charlie Chaplin as „A Woman,“ in a two-reel feature comedy.

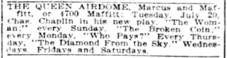

THE QUEEN AIRDOME (...) Tuesday, July 20, Chas. Chaplin in his

new play, „The Woman.“

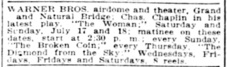

WARNER BROS. airdome and theater (...) Chas. Chaplin in his latest play, „The Woman,“ Saturday and Sunday, July 17 and 18.

(...) St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis, Missouri, July 11, 1915

A Woman is released by Essanay July 12, 1915.

„I learned acting as I learned to read and write“

Editorial content. „Charlie Chaplin´s Story

As narrated by Mr. Chaplin Himself

To Photoplay Magazine´s Special Representative Harry C. Carr

Drawings by E. W. Gale

I am going to reconstruct, as far as possible, Charlie Chaplin‘s

story just as he told it to me, in various little lulls and calms

between pictures, or baths, or dinner engagements, or whatever

seemed to be coming interferingly between us. I found him

a quite, simple, rather lovable little chap, with no especial ambition except to be of entertaining service to the world. He balked

at the idea of writing his own autobiography or having it written

,to sign;‘ said he‘d read fifty autobiographies of more or less

well known people which were just full of words which they‘d never

heard in their lives, so what was the use? But as I said,

I will endeavor to tell his story as nearly in his own words as I can:

Actors trying to write autobiographies are like girls

trying to make fudge. They use up a lot of good

material – such as sugar and ink – and don‘t accomplish

much. Like fudge, the story of a fellow‘s life

ought really to be reserved for his immediate relatives.

If I were Lord Kitchener, doing things and

saying things that made history, I could understand why the

story of my life ought to be written; but I am just

a little chap trying to make people laugh. They are all

so anxious to be happy that they eagerly help me

make the laughs – the audiences, I mean. But they give me all

the credit – not taking any themselves for being so willing

to laugh. So I feel, in a way, that in telling this story, I am just

talking it over with my business partners – the end of the

firm that really makes the laughs.

Some day when I have made money enough out of my

share, I am going to buy a little farm and a good old

horse and buggy – automobile agents can read this part twice

– and retire; sometimes I will ride into town and go

to a moving picture show and see some other fellow making

them laugh.

In the circumstances, I guess you can just put

this story down to this: that Charley Chaplin gives an account

of himself to the firm.

When I was a little boy, the last thing I dreamed

of was being a comedian. My idea was to be a Member of

Parliament or a great musician. I wasn‘t quite clear

which. The only thing I really dreamed about was being rich.

We were so poor that wealth seemed to me the summit

of all ambition and the end of the rainbow.

Both my father and mother were actors. My father

was Charles Chaplin, a well known singer of descriptive ballads.

He had a fine baritone voice and is still remembered

in England. My mother was also a well known vaudeville

singer. On the stage she was known as Lillie Harley.

She, too, had a fine voice and was well known as a singer of the ,character songs‘ which are so popular in England.

She and my father usually traveled with the same vaudeville

company but never, as far as I know, worked in the

same act.

In spite of their professional reputations and their

two salaries, my earliest recollections are of poverty. I guess

the salaries couldn‘t have amounted to much in

those days.

My brother Syd was four years old when I was born.

That interesting event happened at Fontainebleau,

France. My father and mother were touring the continent

at that time with a vaudeville company. I was born

at a hotel on April 16, 1889. As soon as my mother was

able to travel, we returned to London, and that

was my home, more or less, until I came to America.

The very first thing I can remember is of being

shoved out on the stage to sing a song. I could not have been

over five or six years old at that time. My mother was

taken suddenly sick and I was sent on to take her place

in the vaudeville bill. I sang an old Coster song

called Jack Jones.

It must have been about this time that my father died.

My mother was never very strong and, what with

the shock of my father‘s death and all, she was unable

to work for a time.

My brother Syd and I were sent to the poorhouse.

English people have a great horror of the

poorhouse; but I don‘t remember it as a very dreadful place.

To tell you the truth, I don‘t remember much about it.

I have just a vague idea of what it was like.

The strongest recollection I have of this period

of my life is of creeping off by myself at the poorhouse and

pretending I was a very rich and grand person.

My brother Syd was always a wide-awake, lively,

vigorous young person. But I was always delicate and rather

sickly as a child. I was of a dreamy, imaginative

disposition. I was always pretending I was somebody else,

and the worst I ever gave myself in these daydreams

and games of ,pretend‘ was a seat in Parliament for life and

an income of a million pounds.

Sometimes I used to pretend that I was a great

musician, or the director of a great orchestra; but the director

was alway a rich man.

Music, even in my poorhouse days, was always a passion

with me. I never was able to take lessons of any kind,

but I loved to hear music and could play any kind of instrument

I could lay hands on. Even now, I can play the piano,

cello or violin by ear.

Syd had a lofty contempt for these dreams of mine.

What Syd wanted was to be a sailor. He was always pretending

he was walking the bridge of a great battleship, ordering

broadsides walloped into the enemy‘s ships of war.

We didn‘t stay long at the poorhouse. I am not sure

just how long, but my impression is of a short stay. My mother

recovered her health to some extent and took us

back home.

Syd went away from home immediately after we left

the poorhouse. He was really very anxious to be a sailor and

my mother sent him to the Hanwell school, in Surrey,

where boys are trained for the sea. Many boys from the

poorhouse went to this school. I dare say that is

where Syd got the idea.

My mother sent me to school in London. I don‘t

remember a great deal about it. The strongest recollection

I have of school is of being rapped over the knuckles

by the teacher because I wrote left-handed. I was fairly

hammered black and blue on the knuckles before

I finally learned how to write with my right hand. As a result

I can now write just as well with one hand as

the other.

On account of the random way we lived, I didn‘t go

to a regular school very much. Whatever I learned of books

came from my mother.

It seems to me that my mother was the most splendid

woman I ever knew. I can remember how charming

and well mannered she was. She spoke four languages

fluently and had a good education. I have met a lot

of people knocking around the world since; but I have never

met a more thoroughly refined woman than my mother.

If I have amounted to anything, or ever do amount to anything,

it will be due to her. I can remember very plainly how,

even as a very small child, she tried to teach me. I would have

been a fine young roughneck, slamming around the world

as I did, if it not had been for my mother.

I don‘t remember ever having had any definite ambition

to go on the stage or of being attracted to the life.

I just naturally drifted onto the stage. Just as the son of a

storekeeper begins tending to the counter.

With both my mother and father, however, it was

a definite intention to put me on the stage. I can‘t remember

when the talk of this began. It always seemed to be

a fact generally understood in the family that I should be

an actor. I can remember how carefully my mother

trained me in stagecraft. I learned acting as I learned to read

and write.

I don‘t remember when I began regularly as a

professional, but I remember that I was already working on the

stage when I had a narrow escape from drowning.

I remember that I was on tour with a show called

The Yorkshire Lads. It seems to me that I could not have been

much over five or six years old; but I suppose I must

have been a year or two older. Two or three of the boys of the

company were throwing sticks into the River Thames

and I slipped into the stream. I can remember how I felt as I was

swept down the river on the current. I knew that I was

drowning, when I felt a big, shaggy body in the water near me.

I had just consciousness and strength left to grab hold

of the fur and hang on, and was dragged ashore by a big black

woolly dog which belonged to a policeman on duty

along the river. If it hadn‘t been for that dog, there wouldn‘t

have been any Charlie Chaplin on the screen.

I don‘t remember anything about the show I was acting

in at that time. I suppose I must have been acting

or singing at intervals during these years, but the first show

I have any very definite recollection of was a piece

called Jim, the Romance of Cocaine, by H. A. Saintsbury, who

is a very famous playwright on the other side.

This was my first real hit on the stage. I had a part

called ,Sammy, the newsboy,‘ and I will have to admit that between

the part and myself we made a terrific hit.

I got some fine notices from the big London newspapers,

and from that time I began to go ahead.

I liked playing a regular part much better than I did

the vaudeville work. It seems to me that I had made up my mind

at this time to become a legitimate actor. I don‘t

remember that comedy appealed very much to me, either.

I think my parents both had the same ambition for me

that I had for myself. My vaudeville work with them was only

incidental. Both parents being in vaudeville, it was very

natural that I should occasionally be used in one capacity or

another in the show. This is the almost invariable fate

of children of the vaudeville. But, as I remember my mother‘s

training, it was all looking toward a career for me as a

legitimate actor.

The next important part I remember, after appearing

as Sammy the newsboy, was in Sherlock Holmes, in which I had

the part of Billy. I toured all over England in this part

and did well.

After this I began to encounter what Americans call ,hard

sledding.‘ The worst period in my life of a actor starts

as I did is the period between boyhood and maturity. I had

a hard time getting along then. I was too big to make

boys‘ parts convincing and too small and immature to take

men‘s parts.

I will reserve for another chapter my real start as

a grown up actor.

It seems that the story of nobody‘s boyhood is complete

without the account of his boyhood sweethearts. I am

afraid I have nothing thrilling to tell in this regard. I was not the

type of boy who was very strongly attracted to girls

in real life. I was too busy with the people of my games

of ,pretend.‘ Most of my boyhood sweethearts were

wonderful creatures of my daydreams. I have a vague

recollection of certain wonderful charmers of my

own age; but it is not quite clear in my own mind which were

the real little girls and which were the dream children.

The little boy-girl flirtations never appealed to me. The young

ladies available did not live up to the standard

of grandeur set by the young ladies that I imagined.

If, in some way, I have relegated to the mists

of unreality some little girl whom I really adored and whose

name I have forgotten, to her I present my profound

apologies. I will fall back on slang and say that she was

a dream anyhow, which ought to square it.“

Two photos. Seven drawings.

Harry C. Carr, Charlie Chaplin´s Story

Part I, Photoplay, July 1915

Part II, Photoplay, August 1915

Part III, Photoplay, September 1915

Part IV, Photoplay, October 1915

Redaktioneller Inhalt