A Woman Clippings 50/72

Harry C. Carr, Photoplay, New York, September 1915.

Charlie Chaplin impersonator at the Royal Easter

Show, Sydney, Australia, 1916, newsreel, anzacsightsound

& WEST‘S NEW SERIES TO-DAY.

Glaciarium Only

Charles Chaplin in „Woman.“

Charlie Chaplin! That magic name gets ‘em.

Understand? His name smacks of thrills

an‘ throbs. There‘s always something doing when Charlie enters.

De Groen‘s Orchestra

(...) Sydney Morning Herald, Sydney, Australia, Aug. 28, 1915

& THE PICTURE BLOCK THEATRES.

Specials in To-Day‘s Programs. (...)

COLONIAL AND EMPRESS THEATRES.

Showing to-day,

CHARLIE CHAPLIN

in the latest Two-reel Essanay Comedy,

„A WOMAN.“

(...) Sydney Morning Herald, Aug. 28, 1915

„Until it was finally the little toothbrush that is now so famous“

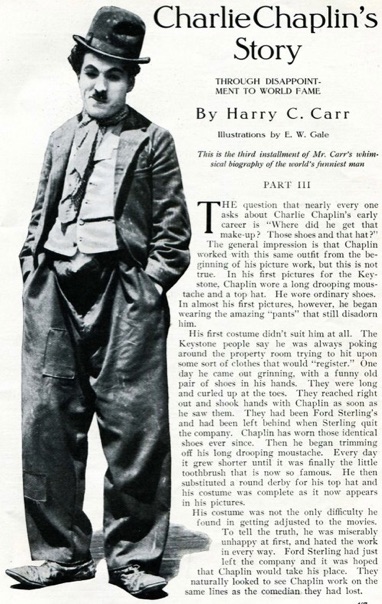

Editorial content. „Charlie Chaplin´s Story

Through Disappointment to World Fame

By Harry C. Carr

Illustrations by E. W. Gale

This is the third installment of Mr. Carr‘s whimsical

biography of the world‘s funniest man

Part III

The question that nearly every one asks about Charlie

Chaplin‘s early career is ,Where did he get that make-up? Those

shoes and that hat?‘ The general impression is that

Chaplin worked with this same outfit from the beginning

of his picture work, but this is not true. In his first

pictures for the Keystone, Chaplin wore a long drooping

moustache and a top hat. He wore ordinary shoes.

In almost his first pictures, however, he began wearing the

amazing ,pants‘ that still disadorn him.

His first costume didn‘t suit him at all. The Keystone

people say he was always poking around the property

room trying to hit upon some sort of clothes that would ,register.‘

One day he came out grinning, with a funny old pair

of shoes in his hands. They were long and curled up at the toes.

They reached right out and shook hands with

Chaplin as soon as he saw them. They had been Ford

Sterling‘s and had been left behind when Sterling

quit the company. Chaplin has worn those identical shoes

ever since. Then he began trimming off his his long

drooping moustache. Every day it grew shorter until it was finally

the little toothbrush that is now so famous. He then

substituted a round derby for his top hat and his costume

was complete as it now appears in his pictures.

His costume was not the only difficulty he found in getting

adjusted to the movies. To tell the truth, he was miserably

unhappy at first, and hated the work in every way. Ford Sterling

had just left the company and it was hoped that Chaplin

would take his place. They naturally looked to see Chaplin work

on the same lines as the comedian they had lost.

Chaplin, however, worked on entirely different methods.

Sterling worked very rapidly, dashing hither and thither

at top speed. Chaplin‘s comedy was slow and deliberate and

he made a great deal out of little things – little subtleties.

They tried to force him to take up the Ford Sterling style and

Chaplin refused. That is to say, he wouldn‘t. He just

listened to what they had to say; then he did in his own way.

The net result was a very sultry time. Chaplin‘s first

director was Pathe Lehrmann. They quarreled all the time during

the first of Chaplin‘s work. Mabel Normand and

Chaplin fought like a black dog and a monkey. Lehrmann

finally appealed to Mack Sennett: he said he couldn‘t

do anything with Chaplin. Sennett called Chaplin to time. The

Keystone people say that the hardest ,call-down‘

anybody ever got at the Keystone was that handed to Charlie

Chaplin by Sennett because he refused to obey

the director. Chaplin took the boss‘s breezy remarks as toasts

to the President are drunk – standing and in silence.

But he went right on acting in his own way. Finally Lehrmann

passed him on to another director, who had an equally

bad time with him.

The Keystone people came to the conclusion that they

had picked up a fine lemon in Chaplin. Personally

he was very popular, but it was generally agreed that he would

never make good as a picture actor.

Finally, Mack Sennett took a hand at directing Chaplin

himself. They were then putting on a piece called

Mabel‘s Strange Predicament. Chaplin had a small part

where he did some funny business in the lobby of a

hotel. Mack Sennett decided to see just what this Englishman

would do if they let him have his own way. He turned

the misfit loose and let him be funny as he liked.

Then and there Charlie Chaplin suddenly ,happened.‘

Mack Sennett saw in a flash that some big stuff

was going over, and from that minute Chaplin became

a real star.

Sennett, during the next few pictures, put in Chaplin to do

little comedy bits that called for some kind of stuff he

showed in the lobby of the hotel. Chaplin was always funny

in these bits, but Sennett saw that, to be entirely

successful he must have a company of his own. The other actors‘

work was out of tune with the Chaplin method. Sennett

was quick to see that almost immeasurable things could be

gotten out of Chaplin, but he also saw that the Chaplin

pictures must, in the future, be built with Chaplin as the foundation.

The whole comedy must be adjusted to his tempo,

and even the scenario would have to be different from

the kind of scenario ordinarily used by the

Keystone people. It must be slower and more subtle.

The end of it was that Chaplin was finally allowed to direct

his own scenarios. No American picture director understood

his peculiar style of comedy well enough to work out the stuff.

In another chapter I will tell about Chaplin‘s work and his

methods as a director.

Chaplin‘s first big hit as a director of his own work was

Dough and Dynamite. This was started as a part of the

scenario afterward known as the Pangs of Love. In his rather

aimless way of directing without any scenario, Chaplin

and Mr. Conklin began working up a play in which both he and

Conklin were in love with the landlady of a boarding

house and stuck hatpins into each other through a curtain

to interrupt one another‘s courtship. They decided

that they both ought to be workmen of some kind and decided

upon being bakers. As part of the play they worked up

a scene in a bake shop. This turned out to be so funny that

they finally changed the whole idea and made two

different scenarios.

As a director-actor at the Keystone, Chaplin had the

reputation of being the most generous star in the

movie business. Every comedian was allowed to grab all the

laughs he could get. Chaplin always insisted on having

them do the comedy stuff in his way, but he always built up their parts

for them without regard for the fact that his own might suffer.

His work began making a tremendous impression. Every one

began talking about the new funny man. People

who never went to the movies before were drawn by the

accounts of the new comedian.

Naturally the other movie companies took notice, and Chaplin

got several big offers. One from the Essanay was so

big that he did not feel justified in refusing. When his contract

expired with the Keystone, he changed companies. He

went with the understanding that he was to have full swing

in his work: direct all his own scenarios and do pretty

much as he pleased.

The first of the Essanay work was done in Chicago.

His first Essanay film was His New Job. After that he put on

a two-reeler, His Night Out. Chaplin then insisted

on moving back to California. The picture conditions didn‘t

suit him in the Middle West. On returning to the Coast,

he went to the Essanay studio at Niles.

In a separate chapter there will be an account of his

adventures at this rural studio. He produced The Tramp at Niles.

This is regarded in some ways as the most remarkable

step forward that has ever been made in moving picture comedy.

Returning from Niles, Chaplin went in the Essanay

studio in an old mansion near the business district of Los Angeles.

Here he has been working ever since. At least this is his

base of operations. From this house he works out to the benches

and various ,locations‘ near Los Angeles.

By this time a perfect storm of fame had struck Chaplin.

To tell the truth, it seemed to scare more than anything

else. He used to say to his intimate friends, ,I can‘t understand

all this stuff. I am just a little nickel comedian trying

to make people laugh. They act as though I were the King of

England.‘ Chaplin even to this day is much alarmed

over being so famous. He says his reputation can‘t last.

But he began to suffer the penalties of the

great. He was asked to speak at banquets; to lead parades;

to referee prize fights. When the baseball season

opened, it was announced that Chaplin would throw the first ball.

All of this stuff worried Chaplin a good deal at first.

He said he picked up the paper every morning with apprehension

to see what fool thing he was due for that day. He found

that it didn‘t worry the promoters of these various events at all,

however. They announced that he would referee at prize

fights, and when he did not appear they simply dressed up a boy

in Chaplin‘s style in clothes and he appeared, serene in the

belief that nobody would know the difference. There is a boy in

Los Angeles who makes a good living by dressing up like

Charlie Chaplin and parading up and down in front of the theaters

where the Chaplin films are being shown.

Charlie was pursued like a wounded bear by all kind

of people with all kinds of business propositions.

If half the life insurance agents who were on his trail could

be gathered into an army, there wouldn‘t be any

danger of a war with Germany. Real estate agents wanted

him to buy houses. Investors wanted him to take

stock in their discoveries. About a million people wrote him letters.

Many of them were mash letters. One young lady

in Chicago undertook the job of censoring all his work. Every

day of her life she wrote Chaplin a letter, commenting

critically on some of his latest films. Sometimes she complimented

them; sometimes she roasted them untenderly.

Chaplin has about as much business system as a chicken.

When his friends came to see him at his hotel they found

him sitting helplessly behind a pile of letters. finally some of his

friends prevailed on him to hire a secretary. Wherefore

a severe young man with glasses now opens Charlie‘s mash

letters.

One sort of pest scared Chaplin to death. This was

the auto agent. They wanted him to buy their cars:

to be photographed in their cars and to write endorsements

of their cars. But Charlie was adamant. He wouldn‘t

listen to any of them. He told them he had an aversion to cars

on principle and when he retired he was going to have

an old white horse and buggy and a ranch. The truth is, Charlie

had once been bitten by an automobile bug.

While he was with the Keystone, Chaplin fell for the

blandishments of an auto agent and came out one day nervously

driving a runabout. He had some weird experience with

that car. He never could learn how the things worked. He knew

how it started but he never could remember – at least

in times of emergency – what you did when you wanted the

thing to stop.

One day while he was parading the boulevards with

his vehicle, Chaplin came to the intersection of two

crowded streets. The traffic cop majestically gave the signal for

the car to stop. Charlie reached for the thingamajig

and pulled the wrong lever. The car bounded blithely forward.

The cop waved his club and that was all he did before

the auto struck him amid-ships and mopped up the floor

with him. They picked up the fragments of the officer

of the law. They also picked up Chaplin and took him to the

police station, where they advised him to learn

how to manage his car and charged him $75 for the advice.

Another time, Charlie was driving in through the big

front gate at the Keystone and got too near one of the posts.

He had been used to sailing small boats. When a small

boat gets too near the wharf the thing to do is to drop the tiller

and fend off by pushing against the wharf. Charlie thought

this ought to apply equally well to a car. So when he saw he was

going to bump the gate, he dropped the steering wheel

and tried to push off from the post. The results were sensational

and startling. Another time, Charlie‘s car was on the

side of a hill. It started to roll down and Chaplin tried to stop

it by grabbing the hind wheels. Results equally

startling and sensational.

When Chaplin discovered that new tires for his motor

cost $75 each, his soul called ,Enough,‘ and he returned to street

cars. Since then he has been a mighty poor prospect

for an auto agent.

Some of the attention that came to Chaplin with his fame

was enjoyable. Thousands of people speak to Chaplin

on the street without knowing him. They are always answered

courteously. Not long ago, I saw two old people stop

and stare and begin to nudge each other in great excitement.

Charlie Chaplin was coming down the street. When

he came near, the old man gathered his courage and said,

,Hello, Charlie Chaplin.‘ Chaplin lifted his hat in the odd

way that he does on the screen and said, ,Howdydo‘ and passed

on. The old people were tickled to death.

The one thing that got the comedian‘s goat was speaking

at banquets. Just once it is recorded that he was prevailed

upon and human agony can have no fuller expression than this

quivering actor waiting to speak his piece.

The culmination of his fame came probably with the offer

of a New York theatrical man to give him $25,000

for an engagement of two weeks – an offer which the Essanay

company is supposed to have met to induce him to stay

away from the stage.“

One photo. Nine drawings.

Harry C. Carr, Charlie Chaplin´s Story,

Photoplay, July 1915

Photoplay, August 1915

Photoplay, September 1915

Photoplay, October 1915

Redaktioneller Inhalt